First attempt at Highscores for games

We are doing our first attempt at implementing online highscores for our games.

Our Score structure right now is:

Score {

id : String - The unique identifier

name : String - The name of the player

points : long - The value of the score

timestamp : date - The time when the score was submitted

tags : Set[String] - A set of tags of the score

data : Map - Extra data of the score

}

The tags are used to classify the scores by different criteria, for example, the difficulty, the level, etc.

Data is a map of simple values used to add extra information of the score, like bombs left when the user died or enemies killed of each type, etc.

The idea is to have an online application for the highscores of all the games. All comunication is performed using a gameKey which is unique for each game and allow us to separate the scores by game.

Our current API consist of a submit method and a query method and it is based in HTTP and JSON.

submit(gamekey : String, name : String, tags : Set[String],

points : long, data : JSONString) : String

This method allows us to submit a new score and returns the generated id for it. The extra data attached to the score is specified by a JSON string. The timestamp is generated at the moment the score is stored.

scores(gamekey, tags, limit, ascending) : List[Score]

This method allows us to query for scores of a game by using:

- tags : returned scores must have every tag in tags

- limit : returned quantity must be less than limit

- ascending : if true scores are returned ordered by points ascending

Our first implementation will be based in google app engine but is not online yet, and Jylonwars will be the first game using it.

There are some features we are thinking about:

- Security: the submitted scores should be encrypted and validated (we know it is not totally safe but it would prevent casual tampering)

- Online scores board

Also, we are thinking about making the server project opensource.</p>

Dassault Dev Diary 3 - Collision Detection

The idea of this post is to share some techniques you could use in order to optimize collision detection in your game, but without implementation detail.

Sometimes when we are developing games, part of our logic could be based on the fact that two objects are in contact or not. In Dasasult, we want to know when bullets are in contact with other objects (for example: droids, scene obstacles or the level limits) and we want to know the area where a droid can walk.

Every object we want to check collisions has a position and a polygon shape defining its form in the collision space. Collision detection between objects is performed by checking collisions between their shapes.

The cost of our collision detection by now is heavy because we are checking collisions between all objects. If we increase the number of objects, then the performance is going to be affected. So, if that is the case, then we could have in mind some optimizations to improve it.

The first one is based on the fact that an object A collides with B then B collides with A and the same when not colliding. We could have a structure to mark whenever we check an object colliding with another object and then use that mark to avoid check the inverse collision. That will let us improve a bit because we will have only half collisions detection but with the cost of memory for the new structure.

The second one is to use bounding boxes for fast intersection detection. The idea is to avoid collision detection between game objects if their bounding boxes are not colliding. The most used shapes for this purpose are: Axis Aligned Bounding Boxes (AABB), Oriented Bounding Boxes (OBB) and Spheres.

For Dassault objects we used AABBs because they are really easy to build and work with.

Bounding boxes are really good when perfect collision is too heavy, but we have a new structure for each object and we have to update it whenever the object changes its position, size or angle.

Figure: droids and obstacles bounding boxes.

The third one is based on the spatial information of the objects to avoid intersection detection with objects far from each other.

Spatial structures are used for this purpose. The idea is to divide the space in zones so we could know in any time, for example, which objects are in a given zone or which zones contains a given object. There are several types of spatial structures: Grids, Octrees/Quadtrees, Binary Space Partitioning (BSP), Kd-trees, etc.

Note: these structures are commonly used for other purposes, for example, frustrum culling and networking algorithms.

For Dassault we used Quadtrees because we have some knowledge of them and a partial implementation to start with, also they work fine with AABBs.

When using spatial structures, we could improve a lot the performance because we can avoid to check a lot of collisions, but also we are growing in the information to maintain and we should be aware that each time an object moves we have to update in which zone is it now. Each spatial structure has its own pros and cons for different cases, you should have them in mind when choosing one for your game.

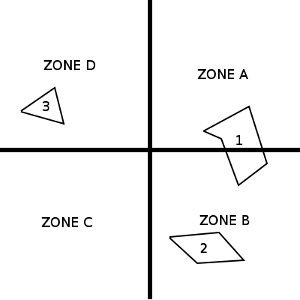

The next example show a possible use of spatial information (using grid partitioning):

Figure: example of objects in different zones

If we take a look at the image, we have object 1 in zone A and B, object 2 in zone B and object 3 in zone D. In one moment we would like to detect collisions for object 1, then we check collisions only with objects in zone A and B, that is, object 2.

After you decided the spatial structure to use, collision detection could be performed like this:

for each object in my zone {

colliding = false

if (getStoredCollision(me, object) != null)

return getStoredCollision(me, object)

else if (collisionBetweenBoundingBoxes(me, object) == false)

colliding = false

else

colliding = perfectCollision(me, object)

storeCollision(me, object, colliding)

return colliding

}

Conclusion

The solution we used worked as we thought and let us to improve a bit the performance of the game. However, the current implementation could be too featureless based on your game requirements, sometimes you need more information from collisions like the points of contact, the movement direction of each colliding object, the normal vector of the contact points for each object, etc. If you want that stuff and more you could use a physics engine, for example, Box2d or Bullet Physics Library (both libraries have Java ports).

Well, hope you enjoyed the post, feel free to make a comment if not.

Dassault Dev Diary 2 - Animations

As I said on the last post, I want to talk about how animations were implemented in Dassault.

In the original game, droids are animated using one image for each frame of the animation. Those images could be all in a single file or not. Here is an example of an animation:

This solution could be expensive for Dassault because droids are rendered in several layers, so to animate a droid we need to animate each droid’s layer.

Another solution, and the one used in Dassault, is to separate the droid in parts to create a hierarchy and then animate those parts by moving them inside the game.

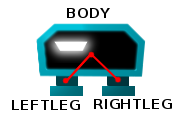

For Dassault, the droids are separated in three parts, the body and the two legs:

And here is an example of how the parts are related to the droid:

droid {

body {

position (0,0)

}

leftleg {

position (-5,5)

}

rightleg {

position (5,5)

}

}

Where each part position is relative to the droid’s position.

To perform the animation, given a specific time, we calculate the value of a property by interpolating the values of two key frames.

For example, we could animate the value of the position of the leftleg part by specifying that on 0ms it should be (0,0) and on 100ms it should be (0,-10) so, when the time is 50ms the position would be (0,-5).

Here is an example of how the animation could be specified:

walk {

body.position {

time 0 (0,0)

time 200 (0,-5)

time 400 (0,0)

time 600 (0,-5)

time 800 (0,0)

}

leftleg.position {

time 0 (0,0)

time 200 (0,-5)

time 400 (0,0)

time 800 (0,0)

}

rightleg.position {

time 0 (0,0)

time 400 (0,0)

time 600 (0,-5)

time 800 (0,0)

}

}

And here is a video showing how it looks inside the game:

This example shows how to animate positions, with the same ideas you could animate an angle, colors, alphavalues, etc.

Next time, I want to talk about collision techniques used for Dassault.

Dassault Dev Diary 1 - Using layers to compose images

Dassault is a game I started for the Game Jolt Demake Contest and it is based on the excellent game Droid Assault from Puppy Games. The contest is already finished but I will keep working on the game with the purpose of learning some techniques (some of them based on the original game) and to share my experience in doing so.

In the original game, the droids are rendered with two different colors if they are from player’s team or not, this is an example:

For Dassault I wanted the colors to be based on each team’s color but when having a lot of teams I don’t want to have one sprite sheet for each one and I don’t want to limit the teams quantity beforehand.

One solution is to have a base sprite sheet and then color it with some script, to generate a lot of sprite sheets. One problem is that it requires a lot of files and that I have to regenerate all of them if something has changed in the base sprite sheet. Also, the number of teams cannot be changed during the game.

Another solution, based on this post from Puppy Games Blog, is to render the droids in several layers, each one with its own color. With this approach, I can paint some layers with one color and the others with default color to make them look just the way I wanted. Here is an example:

+

+ +

+ +

+ +

+ =

=

Now coloring some layers:

+

+ +

+ +

+ +

+ =

=

That was the solution used and it worked right. Inside the game we render the layers in order, to produce the correct result.

To design the images in several layers we are using Gimp. I try different color palettes to see how they’ll look inside the game. Then I save the layers in gray scale exporting each one in a different image file using Export Layers as PNGs python plug-in for Gimp. The images are ready to be colored inside the game.

Here are some screenshots showing how it looks inside the game:

And here you have a video:

You can try the game here. That’s all for now, next time I am planning to talk about animations.

Ludum Dare 17

Hi, we decided to participate on Ludum Dare 17, we are developing two games: Island Warriors, Floating Islands.

We are updating the current state of each game on those two links, we hope we can finish them. You can see other games at Ludum Dare Compo.

The links to play the games are:

UPDATED: added links to play the games and time lapse of Floating Islands.